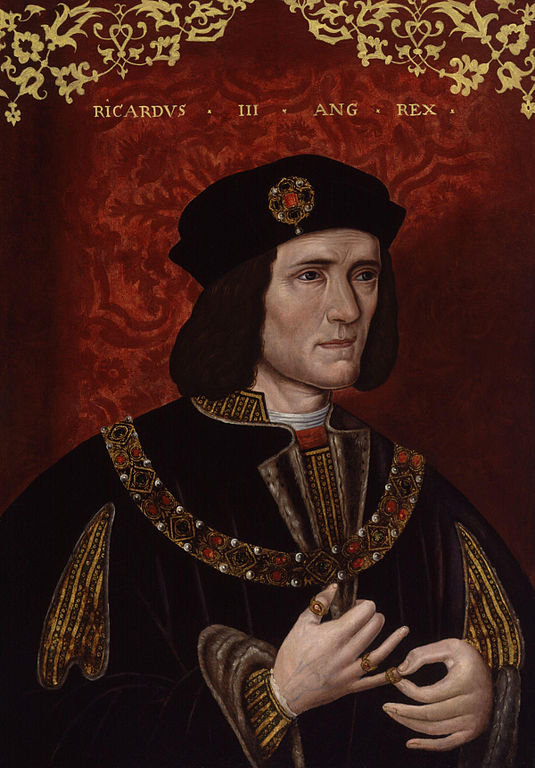

The image most of us have in our minds of King Richard III is of a grotesque hunchback hopping round in the Shakespeare play of that name, whose final line “My Kingdom for a horse” has become his defining byline.

Shakespeare was a great playwright and brilliant rhetorician, but as Graham Mitchell of the Yorkshire Branch of the Richard III Society explained to a packed lecture room in Ilkley’s Manor House in early December, Shakespeare in his history plays was also a ruthless Tudor propagandist.

As Graham suggested, in a forensic analysis of Richard’s life and short reign (1483-5), the facts are far from those presented in either Shakespeare’s play or Tudor histories. Far from being a usurper like his successor Henry Tudor, Richard, younger brother of Edward IV not only had a legitimate claim to the throne, but actually spent many years prior to his accession in active service on behalf of his brother King Edward IV for the people of the North of England. Nor was he a hunchback, but strong, athletic and a brilliant horseman, who fought bravely and successively in several battles to support the monarch, albeit suffering from a curvature the spine we now call scoliosis, which meant that he had uneven shoulders, which were partially compensated by well-designed armour that hid his deformity.

Richard’s links with Yorkshire developed in his teenage years, when he lived at Richard Neville’s fine castle at Middleham, Wensleydale, to where he returned in his twenties in 1473 to live for a decade with his young bride Anne, daughter of the Earl of Warwick. He held the post of Warden of the West Marches – which included much of modern North West England. With symbol of a white wild boar, in effect he was the Governor, on behalf of the English Crown, of most of the North of England as the King’s loyal Lieutenant. As a highly respected Lord Protector and High Constable, Richard soon established himself as a champion of justice and equality before the law, admired by rich and poor alike as a good and fair ruler. As Lord of Scarborough, he ordered building of the borough walls and harbour improvements, encouraging trade from Whitby, Scarborough and Hull. Having been granted the Honour of Skipton, he paid for major improvements to the Parish Church. As King he also became a huge benefactor of York Minster, ordering a new chantry and paying for new altars and living accommodation for priests. He was also a deeply committed Christian. He and his wife Anne were members of the Corpus Christi Guild in York.

When he became monarch in 1483, succeeding Edward V by popular acclaim, he “laid down a coherent programme of legal enactments and actively promoted the well-being of his subjects and use of the English language”. The new King brought about many important, vitally needed legal reforms, ordering that all legal trials should be in English and all jurors have a sound financial basis to avoid bribery. He endowed funds for the building of Kings College Chapel in Cambridge and owned an extensive library including the New Testament in English.

The tragic loss of his son Edward of Middleham in 1484, and his own wife Anne in 1485, meant he had no heir to his throne and was therefore vulnerable to the plotting of his enemies including the Tudors who were eventually able to bring in a large mercenary army, with French support, to defeat Richard’s army at Bosworth in August 1485.

Graham speculated that this almost certainly reflected the resentment of powerful barons in the south about a monarch who spent too much time in the North. They also opposed many of his forward-looking legal reforms.

The murder of the two Princes in the Tower of London was another piece of mythology which Graham suggests can easily be exposed as, for example, there was no evidence of funeral masses for the two victims who almost certainly escaped in secret to either the Continent or Ireland for their own safety, not from Richard, but his actual accusers. Evidence that they survived as potential enemies of the Tudors is compelling, but the “false facts” suggesting that they had been murdered by Richard also made the Tudor succession more secure.

As Graham concluded, History is inevitably written by the Victors. To cement their succession, the Tudors needed to blacken Richard’s name and reputation. His mutilated naked corpse was thrown into a secret grave in a Franciscan Church, now a car park, in Leicester so that it should not be the focal point of future rebellion by Ricardian loyalists. When his bones were discovered and disinterred in 2012, the decision to allow Leicester Cathedral – with no links whatsoever to Richard apart from being close to his final humiliation – to hold his eventual tomb rather than York Minster where Richard had deep personal bonds and was highly regarded, was therefore doubly insulting.

So in a curious way Richard III “the most northern, the most Yorkshire” of all English monarchs and the last Plantagenet English King, forms part of the cultural heritage of Yorkshire we should indeed share with pride – in Scarborough, in Skipton, in York. He was a leader of our province and region whose ideas in the 15th century were far ahead of his southern counterparts, but whose reputation had the misfortune to be destroyed by England’s greatest playwright who understandably was eager to please his Tudor patrons and paymasters.

Reviewed by Colin Speakman, Chairman, The Yorkshire Society.

“The Yorkshire Society. Promoting and Protecting Yorkshire’s Heritage” https://theyorkshiresociety.org